The Classic Way

Storage is the “classic” (and simple) way for retailers to achieve higher margins and offer the cheapest gas among their competitors. It is classic in the sense that many businesses, traders, and consumers utilize “storage” in different ways with different products to their economic and strategic advantage.

Suppose you own a gasoline station (and convenience store) with sales volume of 100,000 gallons per month. You have several competitors within a 5 mile radius, including a big-box retailer that promises the “lowest prices” around. So your gasoline margins are tight and likely to stay that way. You focus on your convenience store products and margins because you think there’s nothing you can do about gasoline margins, right? Wrong. Let your competitors think that.

Now suppose you have an opportunity to install a gasoline storage tank at no cost on your property – no construction, environmental, operating, or any other costs for the tank. It’s free! (It’s also invisible, so you might call it a “virtual tank”.) You can fill the tank with any amount of gasoline at any time (and hold it for as long as you like) to be drawn down at a later date when economically advantageous. Would you install the tank? Do you think having a storage tank filled with, for example, 50% of your monthly sales volume at a price of $1.50/gal or less relative to futures prices that you can draw down at any time will help improve your gasoline margins? Of course it would. That, in essence, is the Storage Road to higher fuel margins.

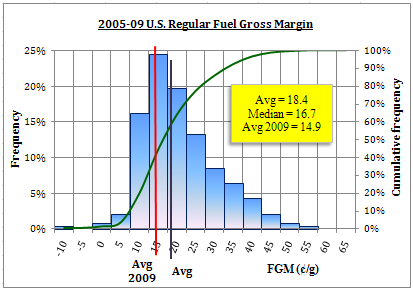

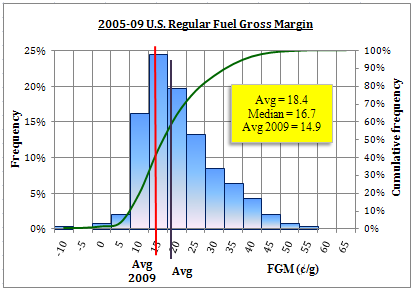

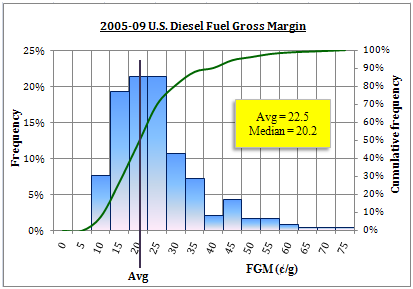

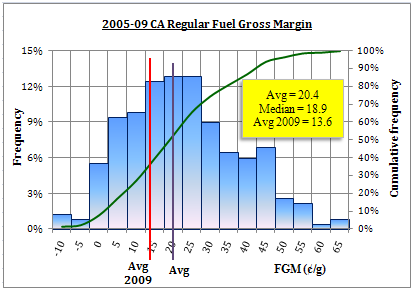

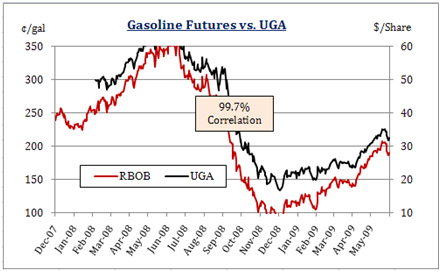

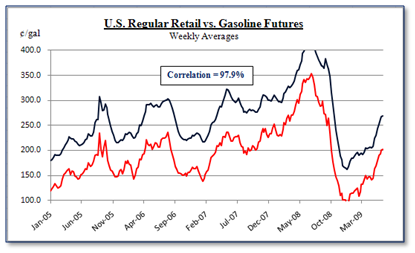

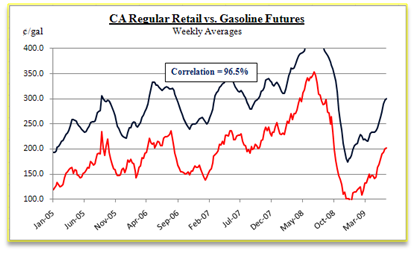

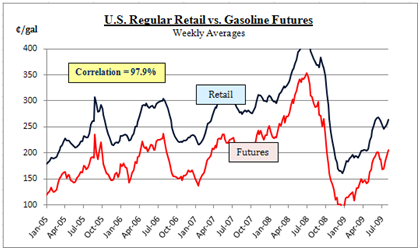

What exactly do you store in the virtual tank? Futures gasoline – the most volatile and impactful component of retail fuel margins (see Post #6) – in the form of futures contracts or “mini-futures” discussed in Post #3. Why store futures? Because futures drive retail prices, as detailed in Post #2 and as the following chart illustrates:

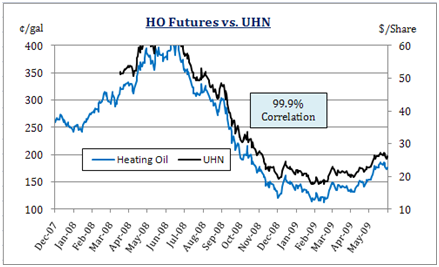

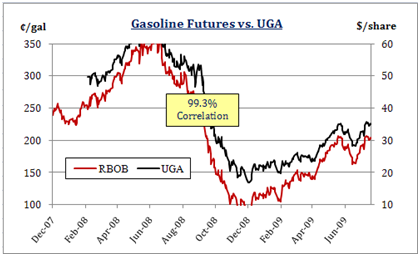

Mini-futures (UGA for gasoline) track futures and provide effective and less costly alternatives to futures contracts (see Post #3) for small volumes. (One futures contract is 42,000 gallons.)

6 shares UGA ≈ 100 gallons RBOB; ± $1/share UGA ≈ ± 6 ¢/g RBOB

Returning to your gasoline station that sells 100,000 gallons per month. Assume it’s January 2009 and you’d like to store 50,000 gallons of gasoline futures in your virtual tank. That’s a little more than 1 futures contract or 3,000 shares of UGA. Assume you store (buy) the 3000 shares of UGA at $22/share. Your virtual tank is “full” – and now you wait for the summer driving season. [This is what makes the strategy “classic”. It’s parallel to a buy-and-hold strategy in the stock market, though the potential holding period is shorter.)

It’s now June 2009 and you sell your 3000 shares of UGA at $30/share. You may decide to keep the profit on your mini-futures or share some of the profit with your customers at the pump. You choose the latter, still achieving higher margins with your mini-futures transaction by pocketing some of the profit, but also scoring points with your customers by truly having the “lowest prices” around (lower than the nearby big-box retailer) and – with the increased traffic to your location due to your low pump prices – racking up more sales in your convenience store.

Specifically, how might you share the profit?

- UGA gain: 3000 shares x ($30 – $22/share) = $24,000

- Share 50% of your gain with customers = $12,000

- Existing monthly volume = 100,000 gallons; assume monthly volume increases 20% due to discounted pump price à new monthly volume = 120,000 gallons

- Allocate $12,000 over July & August à pump price discount (relative to your price without the storage gain) = $12,000 ÷ (2 months x 120,000 gals per month) = 5 ¢/g

Increase your fuel margins, sales, and customers (and customer loyalty) with the Storage road. Offer the cheapest gas “in the neighborhood” and confound your competitors. As Charles Gibson of ABC News said (see Post #5) “… people will drive miles just to save a couple of pennies a gallon.” They may drive twice as far to save 5 ¢/g at your station — and visit your nice convenience store when they arrive.

Next … Options to Protect your Virtual Storage

Posted by TJL

Posted by TJL