Part 2: Making Money

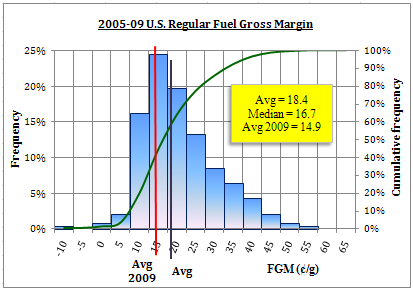

As discussed in Part 1 (Post #4), fuel gross margin must exceed 10 ¢/g for a retailer to profit on fuel sales. Given that, history shows retailers actually lose money on gasoline sales 25% of the time (see the cumulative frequency line on the chart). Weak and unprofitable margins are likely to continue given increased competition and other market pressures.

Fuel retailers leave themselves at the mercy of the market for fuel margins. They react to the most volatile component of fuel cost (i.e. the rack price), their own sales volumes, and what the competition is doing. Is that any way to run a business? Retailers try to make up for low fuel margins with high margin C-store sales. But that “strategy” just masks the problem; it doesn’t solve it. Is the primary business of gas stations to sell gas or store items? Is the reason most people stop at gas stations to get gas or something in the store?

How can retailers directly solve the problem of low fuel margins; i.e. how do they make money on the money margin? As discussed in Post #1, retailers need to be proactive about their fuel margins. Essentially, that just means retailers need to control their rack prices. The easiest and most effective way to control rack prices is to control futures. Remember from Post #2, futures prices set spot prices that, in turn, set rack prices –

Futures prices à Spot prices à Rack prices

Returning to the equation for fuel gross margin:

FGM = Retail price – Futures – Basis – (Rack/Spot differential) – Transportation – Taxes

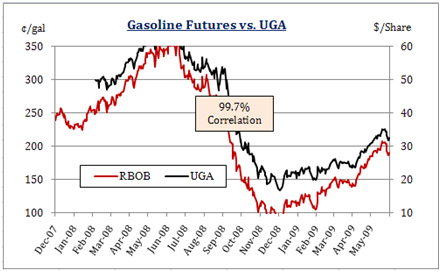

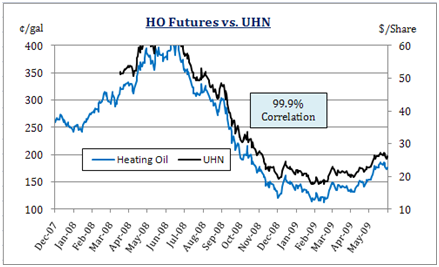

If the Futures price is locked or limited, the retailer controls the most volatile and heaviest potential drag on fuel margins. The futures price may be locked with futures contracts or commodity funds (see Post #3); it may be limited with futures or commodity fund call options. On balance, locking the futures price with a commodity fund (UGA for gasoline, UHN for diesel fuel) is the simplest and most economic choice (e.g. 6 shares of UGA is equivalent to 100 gallons of gasoline futures). A commodity fund may be held indefinitely (like a stock) without the need for “rolling” the position like a futures contract. The fuel retailer may then easily hold the commodity fund until an advantageous time to sell. (More on that “advantageous time” in Post #9.)

The Basis is an important component but less volatile and less of a potential drag on fuel margins. For example, since 2005, the Basis for U.S. gasoline has averaged 4.1 ¢/g with a standard deviation of 8.2 ¢/g. Over the same period, gasoline futures have averaged 195.2 ¢/g with a standard deviation of 56.3 ¢/g.

The Rack/Spot differential is a relatively stable and predictable 1 to 3 ¢/g. It reflects the cost of moving product from spot locations to rack locations, plus the cost of operating a rack.

Transportation is the cost of trucking product from a rack to a retail station. It is also stable and predictable and averages 2 ¢/g.

Lastly, Taxes are a combination of federal and state taxes and are stable enough (though too high!). Taxes by state and product are shown here http://www.api.org/statistics/fueltaxes/.

What’s the bottom line? Control futures and you control the money margin. Control the money margin and you make money selling fuel – consistently and predictably. Even better, control futures and you may increase sales and customer loyalty, and achieve other benefits. That’s called a Fuel Price Protection Program.

Next …

The Roads to Higher Margins: Fuel Card or Storage

Posted by TJL

Posted by TJL